Cleveland Clinic Children’s Rare Genetic Disease Symposium was held on 12 September 2019, with an international faculty and a strand dedicated to informing medical professionals about the rare disease atypical HUS. The aHUS Alliance presentation was among three specific to atypical HUS offered at this recent “MedEd” event held at the Cleveland Clinic, and organized by Dr Rupesh Raina (AGMC, Cleveland Clinic /Research Dir: Akron Nephrology Associates/ Akron Children’s Hospital/ Case Western Reserve University). Dr. Christoph Licht of Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (Canada) spoke on the topic of ‘aHUS, a Genetic Disease: Recent Advancements in Diagnosis and Treatment’, Dr Arvind Bagga of the All India Medical Institute (AIIMS, New Delhi IN) on ‘Orphan Drug Challenges in the Developing World’, and presenting the ‘aHUS Patients’ Perspective’ for the aHUS Alliance was Linda Burke (Maine, USA).

In a room filled to capacity, symposium attendees ran the spectrum from 4th year medical students to seasoned physicians representing varied specialty areas but especially nephrology (both adult and pediatric). Two disease-specific patient organizations were invited to speak at this Cleveland rare genetic disease symposium: the Alport Foundation (Lisa Bonebrake and her son), and the aHUS Alliance (Linda Burke). The agenda for Cleveland Clinic Children’s Rare Genetic Disease Symposium was robust, with speaker presentations followed by a series of 15 minute ‘Hands On’ training in well defined specialty areas. Two “hands On’ sessions were dialysis simulations, including one on dialysis challenges with Dr Tim Bunchman (Prof and Chief of Nephrology at Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU) and one on hemodialysis and SLED-HD Prescription with Dr Rukshana Shroff (Great Ormond Street Hospital, UK) and Dr. Bagga (AIIMS, India).

Click to View (pdf) Rare Genetic Disease Symposium: Program and Workshops

Throughout the day’s presentations several speakers noted issues with accurate and correct diagnosis, the need for more awareness and training for doctors, difficulty in funding research studies and clinical trials, and the effects of healthcare policies and drug access/cost which can impact physicians’ treatment options for rare disease patients. Dr William Smoyer (Dir of Clinical and Translational Research at Nationwide Children’s Hospital/ Prof. of Pediatrics at Ohio State University) ended his talk on advancements for treatment of the rare disease FSGS with an appeal for all present to involve their patients in research. These vital aspects were time and again woven throughout the Cleveland symposium presentations, to include the three aHUS-specific presentations.

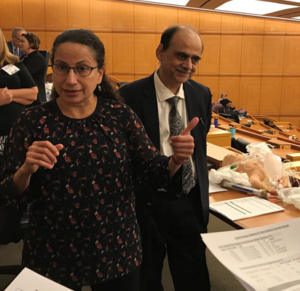

Photo “Hands On Simulation” Session with Dr Rukshana Shroff (Great Ormond Street Hospital, UK) and Dr. Bagga (AIIMS, India). Shown here talking about writing a dialysis prescription: key issues to consider and concerns likely to arise regarding flow rates, fluid volume, etc. Note the dialysis tubing & other teaching materials to Dr Bagga’s right.

Presentation Summaries

Dr Christoph Licht (Canada), Linda Burke (aHUS Alliance), and

Dr Arvind Bagga (India)

12 September 2019

Cleveland Clinic Children’s Rare Genetic Disease Symposium

Dr Christoph Licht – Our Notes

Dr Christoph Licht, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Toronto and a pediatric nephrologist at The Hospital for Sick Children, spoke on the topic of recent advancement in the diagnosis and treatment of atypical HUS. (Program title, aHUS a Genetic Disease: recent advancement in diagnosis and treatment). Four major areas comprised Dr Licht’s presentation: 1) aHUS and the TMA spectrum, 2) aHUS genetics, 3) aHUS treatment, and 4) new diagnostic tests.

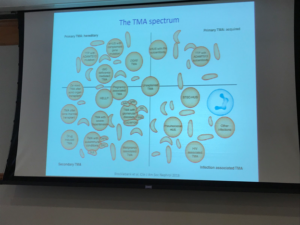

Atypical HUS presents with clinical features similar to other diseases, which makes diagnosis difficult. Dr Licht noted that the terminology surrounding aHUS is confusing, advising that physicians should use caution when reviewing the literature and when treating patients. Physicians need to be aware that various forms of thrombotic microangiopathy can be classified by 4 main types, Inherited or acquired primary; secondary; or infection associated TMAs, which Dr Licht supported by his use of the image below (See Fig 1 from Brocklebank et al. Thrombotic Microangiopathy and the Kidney. CJASN February 2018, 13 (2) 300-317.

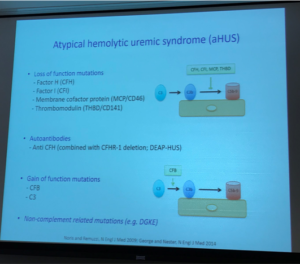

Dr Licht went on to discuss that atypical HUS is a diagnosis of exclusion, and that while some may refer to all forms of aHUS as “complement-mediated” it was important to note that DGKE is not a complement-driven TMA and that should translate into differences in disease management for patients with that genetic profile.

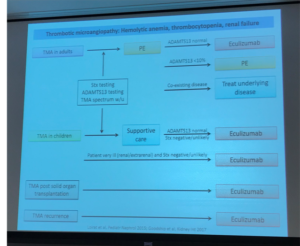

Rapid and accurate diagnosis of atypical HUS is key to promoting positive outcomes for patients. In order to do so, Dr Licht discussed a TMA algorithm (systemic process) to identify diagnosis and treat patients.

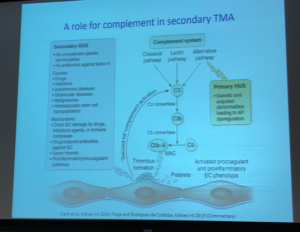

Diagnosis of atypical HUS gets even more difficult when looking at triggers and types of HUS, as well as the role of complement in primary and secondary TMA. The slide below references Atypical and secondary hemolytic uremic syndromes have a distinct presentation and no common genetic risk factors LeClench et al, 2019)

Dr Licht’s presentation at the Cleveland symposium also included an overview of the complement system, as it relates to aHUS and genetics. Genetic mutations can cause disease when the variant does not perform its normal role such as producing a particular protein to regulate complement activity (loss-of-function, as with Factor H). If a gene creates a defective protein with new, different purpose (a gain-of-function mutation) that too could interfere with normal body processes.

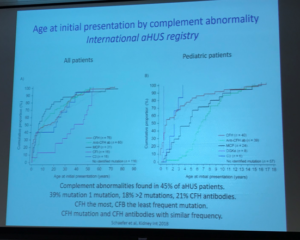

Dr Licht included information from the aHUS Global Patient Registry regarding initial age of presentation, pointing once again to the importance of patients engaging in research to add to the knowledge base of this rare disease. Genetic testing revealed that 45% of aHUS patients had an identified complement abnormality, with 39% having one mutation but about 18% having 2 or more mutations (Factor H most common, Factor B least common).

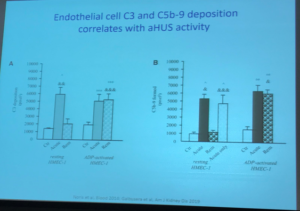

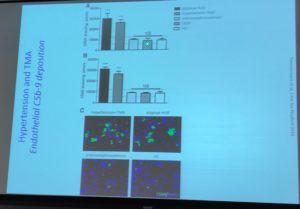

Dr Licht discussed C5b-9 deposition as having potential to guide diagnosis of atypical aHUS, with information from the article C5b9 Formation on Endothelial Cells Reflects Complement Defects among Patients with Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy and Severe Hypertension (Timmersman et al. JASN August 2018, 29 (8) 2234-2243) and others. The aHUS Alliance website has featured several articles related to differentiation among types of TMAs, and has included articles on the impact of aHUS on organs other than the kidneys (extra-renal manifestations), citing this 2015 publication on the topic of C5b-9, An Atypical Case of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Predominant Gastrointestinal Involvement, Intact Renal Function, and C5b-9 Deposition in Colon and Skin.

Two of Dr Licht’s slides on this topic:

Endothelial cell C3 and C5b-9 deposition correlates with aHUS activity

Articles cited:

Noris et al. Blood 2014 Dynamics of complement activation in aHUS and how to monitor eculizumab therapy and also

Galbusera et al. Am J Kid Dis 2019 An Ex Vivo Test of Complement Activation on Endothelium for Individualized Eculizumab Therapy in Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome.

Dr Licht closed his presentation by inviting participants to the upcoming Complement Conference to be held 6-7 March 2020 in Toronto.

Linda Burke – aHUS Patients’ Perspective, presenting on behalf of the aHUS Alliance

The aHUS Alliance appreciated the invitation to share the perspective of atypical HUS patients and patient associations with those gathered for the Rare Genetic Disease Symposium in Cleveland on 12 September 2019. It’s seldom that patients are invited to translate their experiences into efforts that engage and inform physicians, industry, or research. Of the over 7000 rare diseases, about 80% of which have a genetic origin, only about 5% have an approved treatments and those with atypical HUS are fortunate to be within that small group.

There are many common barriers to rare disease research in general, such as small populations, healthcare policies and regulatory environments that vary from country to country, and issues related to data sharing and patient privacy. Research funding, the cost of multiple trial centers, market conditions for drug discovery, and allocation of money for reimbursement (drugs, hospital or clinical care) are some of the economic realities neglected when discussing rare diseases and orphan drugs. Higher patient numbers are more likely to be allocated research dollars and to garner interest. These economics for orphan drugs, the name for drugs used to treat the small numbers of rare disease patients, poses many challenges. Although much is made of the difficulty with low enrollment for studies or clinical trials, the 2016 aHUS Global Poll found that 50% of respondents participated in aHUS research and would again but another 36% had not but would like to know how. (N=233 adult patients or caregivers for pedi patients, from 23 nations).

Over 1 in 3 of the 233 poll participants found most of their information from an aHUS patient organization, and the aHUS Alliance echoed Dr Smoyer’s appeal to involve patients in research and we additionally encourage people to engage with patient organizations. As an umbrella group of national aHUS patient organizations and advocates in more than 30 nations, the aHUS Alliance launched its global aHUS Patients’ Research Agenda on 28 February 2019 (Rare Disease Day). The question of ‘what matters to aHUS patients’ led to establishing 5 categories of research priorities, while including diagnosis and treatment, it broadly covered areas such as socio-economic impact and mental health ( ie anxiety and/or depression).

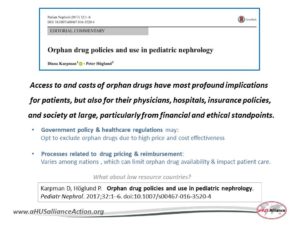

Part of ‘patient-centered care’ is allowing for early and meaningful patient involvement at all stages: policy decisions, research, orphan drug R&D, clinical trial plans, and patient registries. Advancements in medicine take root and grow with involvement of front-line medical professionals, so including the physician viewpoint is essential as well. No matter how wonderful the orphan drug or medical device might be in its ability to save or transform patient lives, what value does it retain in parts of the world where market conditions or high cost make it unavailable to physicians and their patients? Government policy and healthcare regulation may opt to exclude orphan drugs, or restrict their use, due to high cost and cost effectiveness. (D Karpman et al article on aHUS, Cystinosis, and Fabry Disease drug access and cost: Orphan drug policies and use in pediatric nephrology) “Access to and costs of orphan drugs have most profound implications for patients, but also for their physicians, hospitals, insurance policies, and society at large, particularly from financial and ethical standpoints.”.

These issues are key concerns for not just atypical HUS, but for any rare disease. Drug cost may drive the discussion on drug access or restrictive use for eculizumab, but the same issues may likely occur for Ravulizumab (the ‘next gen’ eculizumab currently in late clinical trial phases for aHUS patients).

These are ‘current events’ in the news for Canada, with an August 2019 article in the Financial Post Proposed new drug regulations will hurt all Canadians — and Ottawa has been warned. Canada’s national rare disease organization CORD responded with an article noting that low drug prices can stifle industry and academic initiatives if drug discovery and clinical trials are so expensive that there’s no profit incentive to advance treatment for rare diseases. In Canada rare disease policy varies by province, rather than nationwide, which has led to regional disparities in care for aHUS patients. aHUS Canada has partnered with other stakeholders to advocate for improvements and equity in rare care and treatment. This a case in counterpoint shows the flip side of drug availability tied to economics and impacting national policy. Drug prices that are too high prevent their availability, too low a drug price dis-incentivizes industry drug discovery and the clinical trials needed to bring new therapeutic drugs to market.

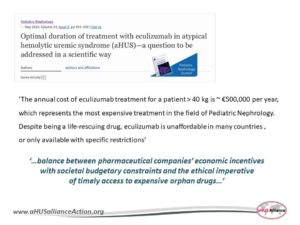

How drug cost drives treatment access is inextricably linked to ethics as well. An excellent article is Optimal duration of treatment with eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS)—a question to be addressed in a scientific way. (G Ariceta, 2019). General barriers for rare disease treatment need to consider finding the balance of economic incentives with socio-economics when ethics is the fulcrum. There’s a lack of data concerning the long-term impact of eculizumab discontinuation.

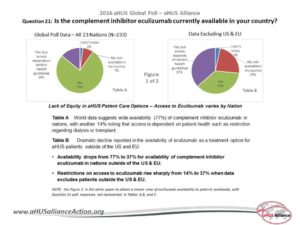

It was important to point out that aHUS patients in most nations do not have access to eculizumab, which likely will mean that they also will not have access when its successor becomes available, the next-Gen drug Ravulizumab. According to the aHUS Alliance 2016 Global Poll, eculizumab availability drops dramatically from 77% (N+ 233, responses from all 23 nations) to only 37% for aHUS patients outside the EU and US. Furthermore, restricted access to eculizumab rose from 14% (all 23 nations) to 37% in nations outside the EU and US. Restricted use is often for drug access for limited time periods, or for specific patient profiles. Excluding aHUS patients on dialysis is the most common restriction, and one that effectively blocks kidney transplants and subjects aHUS patients to a lifetime of dialysis. In actuality, lack of equity in drug access and patient care becomes more grim with larger, scientific sampling and robust methodology inclusive of more nations.

Drug cost limits availability. It’s that simple. For developing nations or countries with low resources, drugs like eculizumab simply are not available. Some nations are still in their infancy when it comes to rare disease policy, but many simply concentrate are larger public health issues such as clean water or infectious diseases that broadly affect their nation. Imagine the ethical implications and hard realities that fact physicians who know a life-transforming drug lies just beyond their nation’s borders? As a possible solution we presented the Global Review Panel Model for aHUS Drug Access, created by physicians in South Africa, Dr Mignon McCullogh and Dr Errol Gottlich in affiliation with the aHUS Alliance. Scarce resources need thoughtful management, and careful distribution. Engaging patients and physicians to gain input at the earliest stages of drug development can provide valuable insight, including marketplace factors. Discussion continued with the value of expert physicians central to this model, and utilizing this organizational model to reap multiple benefits for all stakeholders.

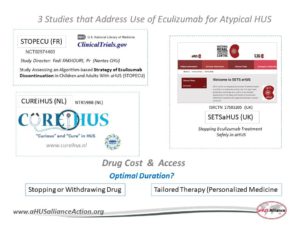

Might personalized medicine, or an approach ‘tailored’ to a patient’s individual medical profile, lead to more effective treatment and to reduced cost? What’s the optimal duration for treatment, and under what circumstances (and with what risks) can eculizumab be discontinued? What about long term follow up (longitudinal) studies of for such patients? What would restrictive use parameters look like, and would such restrictions help the economic picture, impacting drug access in a positive manner? Evidence-based data is needed. We mentioned 3 studies that are addressing these questions, in nations which have an active aHUS Alliance advocates and patients as partners.

STOPECU (France), SETSaHUS (UK), and CUREiHIS Studie (NL) and a publication.

In 2011 eculizumab was approved in the USA to treat patients with atypical HUS, but it wasn’t until 2015 that NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) did the same for patients in the UK. It was a long and challenging road for aHUSUK, the patient organization to bring eculizumab to the UK but provides a road map for aHUS groups in other nations who seek to change drug policy in their own country. The aHUS Alliance series The Reluctant Advocate details the many setbacks until aHUS patients and family caregivers in the UK successfully worked together with researchers, physicians, kidney and rare disease groups and other stakeholders. Part of the NICE process required a review of drug effectiveness and treatment recommendations, and the SETSaHUS study will provide data for the UK government’s NICE review.

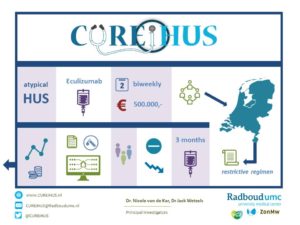

In 2016 the Dutch government balked at the concept of reimbursement for eculizumab as a lifelong drug. The NL CUREiHUS study has about 50 aHUS patients in its database, with the goal to determine optimal duration and treatment strategies. The Dutch working group has early results indicating that most aHUS patients do not need a biweekly dosing schedule, but patients are closely monitored and are assessed for potential risk factors. Their guidelines seem cost-effective, and the Dutch study team estimates a eculizumab cost reduction of 24 million euros (60%) compared to the EMA (European Medicines Agency) treatment plan. The results of switching to an extended dosing interval or withdrawing eculizumab is expected in the spring of 2021. aHUS NL and kidney advocacy group NVM have shared insights, and will continue to play an important role in determining the future of aHUS treatment in the Netherlands.

The aHUS Alliance presentation closed with a series of three slides on needs to keep ‘Moving Forward’: 1) Addressing Knowledge Gaps, 2) Rapid & Accurate Diagnosis, and 3) Appropriate and Affordable Therapy. Connecting information underscores all areas, and to do so collaboration is key. Variations in aHUS presentation and clinical profiles range widely, diagnosis is difficult, and compounding these are confusing terminology and classification. Educating physicians in critical care settings can with early determination of appropriate treatment. Across the TMA spectrum and certainly for atypical HUS, patients may be assigned a primary specialist in one of several fields: nephrology, hematology, heme-onc, immunology, or other areas. Collaboration and communication is essential. Establishing multi-disciplinary TMA teams at hospitals and in clinics can serve to promote better patient outcomes, especially for those with extra-renal involvement and for secondary aHUS. Early identification of aHUS patients may help save kidney function, allowing organ allocation to concentrate on kidney diseases for which there is no treatments, and perhaps additionally improve enrollment in studies and in clinical trials. Fragmented information flow and outreach, further impeded by a lack of connectivity, means lost opportunities on multiple fronts.

The aHUS Alliance presentation closed with our sincere thanks to all attending and to Dr Rupesh Raina for organizing the symposium and including the aHUS Patient Perspective. We especially appreciate the continued efforts of Dr Raina, Dr Licht, and Dr Bagga who each share their expertise within the global network of aHUS Clinicians & Researchers.

New Publication: More on the aHUS Patient Perspective, see pg 188

Optimal management of atypical hemolytic uremic disease: challenges and solutions

Dr Arvind Bagga – Our Notes

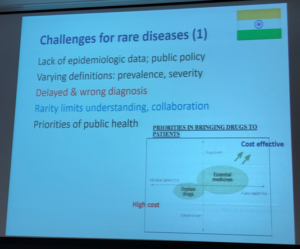

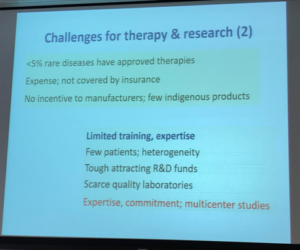

Dr Arvind Bagga, Prof at the ICMR Center for Advanced Research in Nephrology/ Dept of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, spoke on the topic of ‘Orphan Drugs Challenges in the Developing World’. Rare diseases face some common challenges around the world: low patient numbers, high expense per patient ratios, limited training and few with expertise in specialized areas.

The definition of what constitutes a rare disease varies around the world. It’s more difficult to collaborate when rarity limits both understanding and opportunity. In India rare disease challenges include aspects that affect other nations, such as delayed or incorrect diagnosis, but India must consider cost when establishing priorities in bringing drugs to patients. Orphan drugs are high cost for small patient populations, whereas essential medications treat larger numbers of patients for much lower costs and are therefore most cost effective.

Drugs to treat rare disease patients generally are made outside of India, leaving few incentives for manufacturers. This has created a lack of quality laboratories in India, another factor making it difficult to attract funding for research and development. While commitment and expertise can provide leverage to help alleviate such challenges, multi-center studies can be a practical solution.

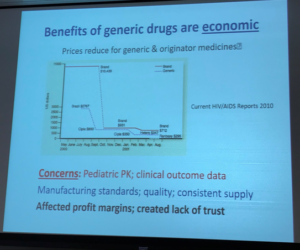

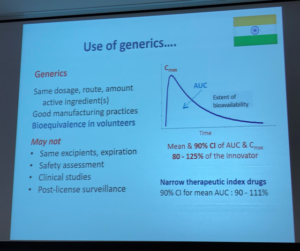

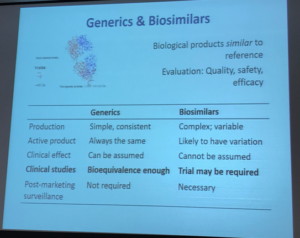

Generics and biosimilars can help reduce cost, therefore expand what physicians in India have available as treatment options for their patients. Dr Bagga’s presentation included multiple slides on this topic, as seen below. At its most basic, generic drugs are chemical copies of the original drug. These are often simple molecular compounds that can be replicated from the ‘originator’ or ‘reference drug’, after the medicine’s drug patents expire, to copy the drug’s safety and effectiveness. A biosimilar drug is much more challenging to re-create.

The aHUS Alliance has great interest in this topic. Conventional medicines are usually made or synthesized as chemical compounds, and are made by following a specific chemical mix combined in set quantities. Pharmaceutical companies that bring a conventional drug to market have their investment costs for research and development protected by patent laws for a set period of time, which allows the company to garner profits from their work. Once the patent legally expires other companies can enter the market with a chemical composition identical to brand name drug, called a generic. The process is different for biologic drugs since they are derived from living animals and microorganisms. Living things are complex in form and function, with each lifeform differing from others of its type. While it’s relatively simply to copy a chemical formula and synthesize a generic version of a conventional drug, it’s not possible to create exact copies of a living thing. With biologic drugs, pharmaceutical companies attempt to create a highly similar drug which will be both safe and effective (a biosimilar) to a specific drug that came earlier (the ‘reference drug’, such as eculizumab) – but a biosimilar is not an exact duplicate of its reference drug.

Dr Bagga provided an excellent rationale for why the reduced costs for generic and biosimilar drugs can help developing countries and low resource nations with a pathway to provide expanded treatment options.

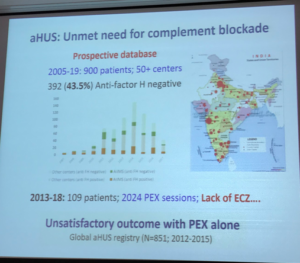

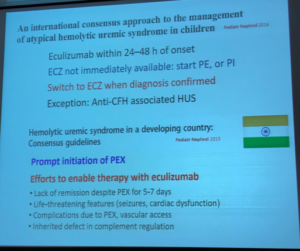

For patients in India with aHUS, few treatment options exist other than the supportive care of plasma therapies, such as plasma infusions (PI) or plasma exchange (also called plasmapheresis, PE/PEX). From 2005 through 2019, there were 900 patients at over 50 centers, with about 43% identified in that database as anti-factor H negative. From 2013-2018, 109 atypical HUS patients in India had 2024 plasma exchange sessions (PEX), which is a sub-optimal approach with correspondingly poor patient outcomes. Clearly the unmet need for a complement inhibitor (such as eculizumab) and global guidelines for aHUS treatment are not followed due to lack of drug access due to high cost. International consensus for pediatric aHUS patients clearly outlines ‘best practices’ to be followed for children in all nations, not just those nations who can afford the drug.

Dr Bagga continued his presentation by noting that India is not alone in having high orphan drug cost limit availability, nor are aHUS patients the only rare disease group negatively impacted due to economics and national policies. In South Africa, the allocated cost for patient healthcare in US dollars is $670 while in Brazil the national cost per patients is $1,119. By stark contrast, India allocates a mere $62 per year. Consider the ethical implications faced by physicians and patient families in low resource nations.

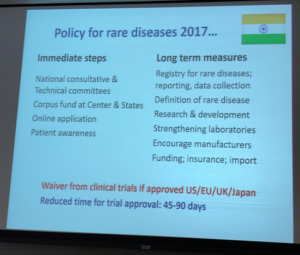

In addition to noting the ability of generics and biosimilars to reduce costs and expand access for rare disease patients, Dr Bagga mentioned India’s work over the last dozen years to strengthen patent and IP laws and to create short- and long-term steps to resolve rare disease issues.

In the 1970s, ‘reverse engineering’ lead to concerns for manufacturing standards, drug quality controls, and creating a safe and consistent chain of supply. India now has rare disease legislature to create a more welcome environment for research and clinical trials. One policy change is that India does not require further clinical trials is a drug is already approved in the US, EU, UK, or Japan. Improvements in rare disease policy, patent laws and IP protection greatly improves incentives for industry, and work to ensure a safe and adequate drug supply. The economic facts remain, but the equity in rare disease treatment still exists. India is working to overcome challenges, including better laboratories, but a collaborative approach with innovative partners is still needed to bring lower cost complement inhibitors to India.

Moving forward … what insights did this conference provide?

The registration response to the Rare Genetic Disease Symposium in Cleveland was overwhelming, with a capacity crowd and a very long wait list held in reserve in the event of any cancellations. This would indicate the need for inclusion of such topics at future ‘MedEd’ and medical conferences, to perhaps include an expanded program at the Cleveland Clinic in 2020. There was high interest among the medical residents and fellows, so how might teaching hospitals include a rare disease component?

Hospitals, rare disease stakeholders, and a variety of organizations need to consider they may weave into their own initiative these rare disease threads that ran throughout this 12 Sept 2019 program in Cleveland.

In all, it was very telling that the aHUS Alliance website banner neatly encapsulated common messages underscoring the program and presentations on 12 Sept 2019. To move forward, together we need to *Connect *Inform *Collaborate.

![]()