Those new to the disease aHUS may not know the significant contribution that Dr Leonard Bell has made to their treatment today. Leonard, or Lenny as he was called , retired from active work as CEO of the company he created. That was nearly nine years ago , or seven years if you include his time as Chairman of the Board of Alexion Pharmaceuticals.

Unlike Alexion, or Astra Zeneca Alexion, leaders today Lenny was more than a “professional Pharma executive”. Lenny actually conceived and developed the company’s product that eventually made such a difference to the lives of aHUS patients.

Born in the late 1950s, in his early twenties Lenny was a student at the University of Yale School of Medicine having gained his first degree at Browns University. This began a long connection with the city in which Yale is located, that is New Haven, Connecticut. Once qualified as a doctor he developed a specialism in cardiology and practiced at the Yale New Haven Hospital. He also held a position as Assistance Professor at the University of Yale School of Medicine.

By his early thirties he was well established in academia and medical practice. But he enjoyed his time in Professor Joseph Madri’s laboratory at the School of Medicine along with others who like Lenny would talk about creating their own biotechnology company one day.

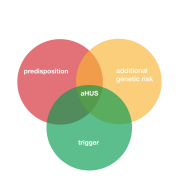

At this time Lenny became interested in the immune system particularly a little known part of the innate immune system called complement. He began to see that complement played roles which were good but some times it turned bad and it became the cause of inflammatory disorders. He became interested in using monoclonal antibodies to tackle diseases caused by complement.

Monoclonal antibodies, or mAbs ( with a capital “A” for some reason), had been around since 1975. So Lenny did not discover them nor did he create the first mAb to block C5 which was the complement component of most interest to him. In 1987 a research group in Basel, Switzerland did that by providing proof of concept that a mAb could be created to block the activity of C5 in a mouse model. A monoclonal antibody or mAb targeting C5. It had the name B5.1.1. Lenny and his collaborators’ focus was on “humanising” that Swiss mAb and developing it as therapy for complement mediated diseases.

So the fantasy of creating a biotech company became a reality to do just that after a meeting with six colleagues at the Omni Hotel in New Haven in December 1991. On 28 January 1992 Lenny and two other lab collaborators Professor Joseph Madri, and Dr Stephen Squinto, as well as Dr Scott Rollins co founded a company to be called Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

The others involved in the Omni Hotel meeting, Dr Jospeh Frie, David Keuse ,and Louis Matis would also join the company as senior employees. Prof Madri , although a founder, would remain in his Department at Yale Medical School. So Alexion started with five employees. Each of these employees would each receive an annual salary of $1.5million ( at 2024 US dollar purchase power) each. Others, like young researcher Russell Rother from Oklahoma would join Alexion later that year. The company leased some premises at Suite 360 , 25 Science Park, New Haven. Lenny would say later that those premises were the kind for businesses which “started out small but had big ideas”

The leases would cost $6000 per month. Suite 360 would house a laboratory for research, equipment to produce the monoclonal antibodies and an area for administration. Although the bulk of a fledgling bio tech company work surrounds the science, there are lots legal activities that come with it, including patent applications , licensing , legal compliances and grant/financial work. Not least raising the funds for the company to survive while it had no products to sell

So work began on potential mAb therapies for treating complement disorders particularly focussing on those resulting from C5a inflammation and uncontrolled complement membrane attack complex and the component C5b-9. To do that an effective “humanised version of the C5 mAb B5.1.1, which could only work in mice not humans, was needed. What they needed to do was to create a “lizumab” – literally a immunomodulating humanised monoclonal antibody in the drug naming world .

The next four years of research involved creating a panel of over 30, 000 potential lizumAbs from the B5.1.1 version and testing them for the ability to block human C5 and engineering them so that they could be used on humans. Looking for one that was effective in inhibiting C5 but would not itself be destroyed by the human immune system. Lenny’s research team used existing technology to do that after acquiring a B5.1.1 mouse.

Eventually one candidate was found called 5G1.1 and a variant of it 5G1.1-SC

From studies they also knew that the half life of the 5G1.1 in its blocking C5 doses was 272 hours plus 82 hours ( nearly 15 days). So a potential complement therapy had been created. In fact two mAbs, .

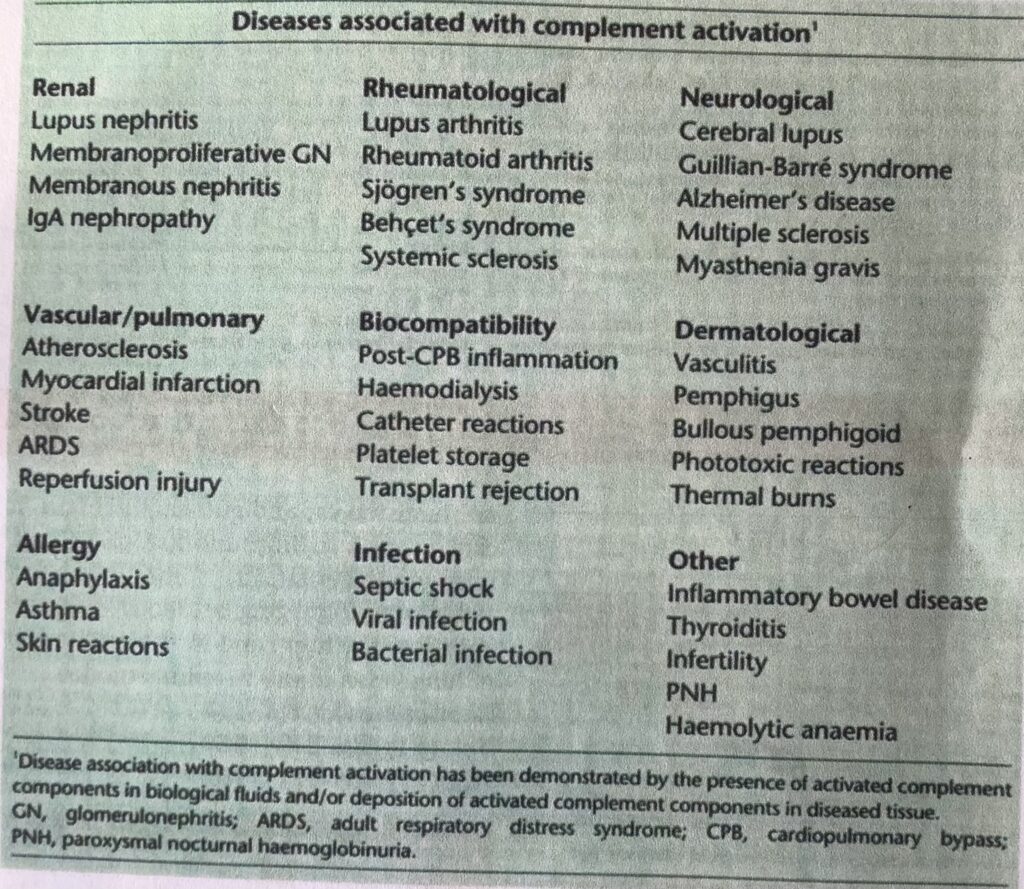

Further research on complement mediated diseases was undertaken to chose candidates for pre clinical studies. This table in a research paper (1995) by Lenny’s team lists potential candidates for trialling the “lizumabs” they had created.

Though there is a mention of PNH ( paroxymal nocturnal hemoglobinurea) in the “other” category there is no mention of aHUS in a 1995 publication by Alexion. Although at that very same time over in England a research team including Paul Warwicker was about to start a study of complement dysregulation as a genetic cause of aHUS but their breakthrough findings would not be published for another three years.. ( More about that in a previous article in the Before aHUS Endeavours Fade series see end of this article for a link)

Lenny and his Alexion team chose to focus on vascular and immunological conditions. 5G1.1-SC or pexelizumab as became known would be looked at for post heart lung by pass surgery inflammation and myocardial infarction. Lupus and Rheumatoid Arthritis would be investigated in pre clinical studies of 5G1.1. Both drugs designed to ameliorate these diseases by blocking C5. Their studies suggested they would. So major clinical studies would be needed next. Trials would require thousands of human participants , these were common diseases but were “orphan” in that there were no effective treatment.

By 1995 Lenny’s company had 45 employees and had accumulated nearly $50million in losses, it had $30 million still to invest in research but it was not enough. Its only income, about $2 million, was from some side research on behalf of the US Surgical Society on immunosuppression to prevent graft rejection of pigs’ organs after transplant.

Up to that point capital funds had been raised through public and private sales of share equity.

Money was needed to do that. So in 1996 the company was listed on NASDAQ exchange to raise funds for the next part of journey. This was a step change and a risk for investors because if clinical trials failed there would be no product sales and the company would die with debts and little of investors investment would be returned. Failure to find suitable products to sell would expose the founders of the company to bankruptcy.

Trials did take place by the turn of the century pexelizumab had become Alexion’s priority becoming a collaboration with Proctor and Gamble. In 2000 Alexion moved to new leased premises at 350 Knotter Drive in Cheshire , Connecticut.

Trials for pexelizumab involved up to 3000 patients for the heart by pass studies and heart attacks. There were 600,000 by-pass surgeries and 1 million heart attacks in the USA each year. Similarly 5G1.1. needed large numbers of patients for Rheumatoid Arthritis studies ( prevalent patient population in USA 2 million) About 40 were being studied in the treatment of Lupus. Both drugs showed promise but while the company was pursuing its pexelizumab /5G1,1 trials in 2002 a small project in the lab run by an Alexion employee in collaboration with a hematologist from a hospital in Leeds in the north of England, UK. would become more significant. It was an application of 5G1.1 ,or eculizumab as it became named in January of that year, for treating that rare life life threatening disease called PNH. The hematologist was Dr Peter Hillmen ( see photo right) and the Alexion employee who was instrumental in there being a PNH programme was Russell Rother, one of the original scientists to join the company in 1992.

During 2002 the researchers in the Leeds hospital had commenced a pilot study with eculizumab in patients with PNH and the first patient was recruited in May. Two more FDA approved phase 3 clinical trials followed. These were successful and by 2006 the drug was licenced for use to treat PNH in USA and Europe. Alexion begins to receives income from sales of its one and only product at that time eculizumab. By this time over $800million funds had been raised and it had not made any profit!

Russel Rother

Pexelizumab and the other conditions lost their preference to eculizumab in Alexion’s eyes and were slowly “forgotten” over those years. The company had to become a world wide sales and distribution company not just a drug development company.

Eculizumab created an enormous stir of interest in 2002 and that December the results of the pilot study were revealed at the American Society of Haematologists, ASH . This was followed by many articles about it and PNH , Hillmen and Rother featuring quite often in them.

By 2007 over $800million had been invested to produce a single product for one rare disease. At an annual cost per patient of $400,000 which was regarded as top of the most expensive drugs by Forbes magazine in 2010.

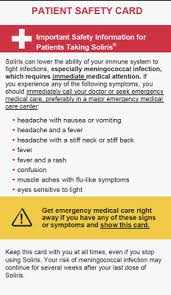

The first public mention of aHUS being a target for eculizumab was in October 2008. The first clinical trial of eculizumab for aHUS would not commence until April 2009. Who or what was behind the translation of research to aHUS from 2002 to that major event for aHUS patients everywhere is not clear. The first published article about an aHUS patient receiving eculizumab was a case study published in January 2009.

One of the two authors was Russell Rother. Coincidence?

Without Dr Leonard Bell’s vision , leadership and risk taking the aHUS world probably have been a lot different today. Equally the parts played by mostly unknown team members, like Russell Rother, were instrumental in saving the lives of many unknown people around the world.

In 2024 Dr Leonard Bell is 65 ,retired and is very wealthy. He is involved as a trustee of a non profit called “The Linda and Lenny Bell Family Foundation”

Article No 639

Previous articles in the series.

The early days of aHUS Research (Before aHUS Endeavours Fade)

Global Action is privileged to present a second article in the series BEFORE aHUS ENDEAVOURS FADE. Celebrating the work of people whose research made a significant difference for aHUS patients.…

CONTINUE READINGThe early days of aHUS Research (Before aHUS Endeavours Fade)

Before aHUS endeavours fade

There have been moments and events in the past where someone whose endeavours make a significant difference for those who have been diagnosed with aHUS today. This is about one.…